Bridging Gaps: Addressing the Factors That Shape Cancer Risk and Outcomes

The crosscutting issues affecting cancer control in Nevada can be attributed largely to social determinants of health (SDoH), including access to healthcare, public health infrastructure, race and ethnicity, and environmental factors.

A two-track approach to overcoming the negative ramifications of SDoH in cancer control involves both mainstreaming these issues into all policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) change initiatives and implementing targeted interventions to address specific challenges. This dual strategy ensures that crosscutting issues like health equity, climate change, housing, and food insecurity are considered at every stage and level of community action, rather than being treated as isolated concerns.

Strategies to address crosscutting issues are embedded throughout this plan to ensure solutions benefit all Nevadans, and targeted interventions are recommended to address unique challenges faced by particular groups, such as supporting access to culturally affirming and trauma-informed care.

What is trauma-informed care?

Trauma-informed care is a framework for understanding and responding to the effects of trauma in individuals, systems, and organizations. It aims to create safe and supportive environments that promote healing and recovery for people who have experienced trauma.

Cancer Doesn't Affect All Nevadans Equally

Racial and ethnic disparities persist in cancer screening, diagnosis, and outcomes.

Learn More About:

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, shaped by factors such as income, education, geography, access to healthcare, and social environments. These non-medical determinants play a crucial role in cancer risk, prevention, detection, treatment, and survivorship in Nevada. Recent researchiii has found that SDoH may contribute to up to 70% of cancer cases and should be a significant focus, alongside clinical interventions, for cancer control efforts.

Key SDoH factors in Nevada include:

- Race and Ethnicity

- Health Literacy and Education

- Housing and Food Insecurity

- Access to Healthcare and Geography

- Income and Insurance Status

- Public Health Infrastructure

- Environmental Exposures

Race and ethnicity as a SDoH reveal disparities that are not simply the result of biological differences but reflect a complex interplay of social, economic, environmental, and systemic factors. People who are racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be uninsured, be of lower socioeconomic status, and have lower health literacy and trust in the healthcare system. They are also more likely to face discrimination in the healthcare system, in part because of a lack of racial and ethnic diversity in medical professions and a lack of representation in clinical research.

Racial and ethnic disparities persist in cancer screening, diagnosis, and outcomes. Individuals from minority populations, including Black and Hispanic communities, are less likely to undergo recommended cancer screenings, such as those for colorectal cancer.ix For certain malignancies, including breast and prostate cancers, Black individuals are more frequently diagnosed with more aggressive tumor subtypes compared to their white counterparts.x Early detection is particularly critical for these cancers, as it increases the likelihood of successful treatment. Notably, while Black women in Nevada are more likely to be screened for breast cancer than white women,xi they continue to be diagnosed and die from the disease at much higher ratesxii highlighting ongoing inequities in cancer outcomes despite timely screening.

Other people who are part of racial and ethnic minority groups may have language and cultural barriers that can keep them from accessing healthcare. This is compounded by a complex healthcare system that at times doesn’t take into account individuals with lower health literacy. The use of plain language, translators, multi-lingual and culturally tailored materials, and navigators can be solutions to these challenges,xiii but must be broadly applied to create a system that is both welcoming and accessible for all Nevadans.

iii Yu, Z., et al. "Assessing the Documentation of Social Determinants of Health for Lung Cancer Patients in Clinical Narratives." Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 10, 2022, Mar. 28, doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.778463.

ix Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2022, www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html.

x Chen, Y., et al. "Breast and Prostate Cancers Harbor Common Somatic Copy Number Alterations That Consistently Differ by Race and Are Associated with Survival." BMC Medical Genomics, vol. 13, no. 1, 2020, Aug. 20, doi:10.1186/s12920-020-00765-2.

xi Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2022, www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html.

xii Nevada Central Cancer Registry. Five-Year Cancer Incidence and Mortality and Stage at Diagnosis, 2018–2022.

xiii Andrulis, D. P., and C. Brach. "Integrating Literacy, Culture, and Language to Improve Health Care Quality for Diverse Populations." American Journal of Health Behavior, vol. 31, no. Suppl 1, 2007, pp. S122–33, doi:10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S122.

Housing and Food Insecurity

Housing and food insecurity have sharply increased in Nevada over the past decade with significant consequences for cancer prevention, treatment, and outcomes. Housing costs have outpaced income growth across the state, and Nevada now ranks second in the nation for cost-burdened renters and fifth for excessively cost-burdened homeowners. Extremely low-income households have fewer affordable housing options than any other state.xiv Data from the CDC shows an average of nearly 13% of Nevadans across all counties are housing insecure. Additionally, research from Feeding America shows that 15% of Nevadans are food insecure, and in some rural counties 18-22% of residents are food insecure.xv

Insecure housing and lack of nutritious food can lead to chronic stress, which is linked to biological changes that can increase cancer risk and progression. Additionally, they can lead to unhealthy behaviors, such as tobacco and drug use, sedentary lifestyle, and poor diet, further elevating cancer risk.xvi Both issues can also create a situation where an individual must choose between basic needs and healthcare, resulting in skipped and postponed appointments, delayed treatments, and poor medication adherence. The lack of stable housing can also lead to frequent moves resulting in the lack of a regular healthcare provider and foregoing recommended cancer screenings, reducing opportunities for early detection.

Researchers have found that people who are unhoused have a cancer incidence four times higher than those who are housed and mortality rates twice as high.xvii The financial burden of cancer care can further destabilize those who are already struggling to meet basic needs, and cancer survivors with housing and food insecurity face greater difficulty in managing their health, leading to poorer quality of life.

xiv Guinn Center for Policy Priorities. Housing Affordability in Nevada: An Economic Analysis and Policy Considerations, Feb. 2025, www.guinncenter.org/research/housing-affordability-in-nevada-an-economic-analysis-and-policy-considerations.

xv Feeding America. Map the Meal Gap: Food Insecurity among the Overall Population in Nevada, 2023, https://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2023/overall/nevada.

xvi Fan, Q., et al. "Housing Insecurity Among Patients With Cancer." Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 114, no. 12, 8 Dec. 2022, pp. 1584–92, doi:10.1093/jnci/djac136.

xvii Howard, L., and J. Bourgeois. "Impact of Housing, Food, and Transportation Insecurities on Patients With Cancer." Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, vol. 29, no. 2, 14 Mar. 2025, pp. 170–73, doi:10.1188/25.CJON.170-173.

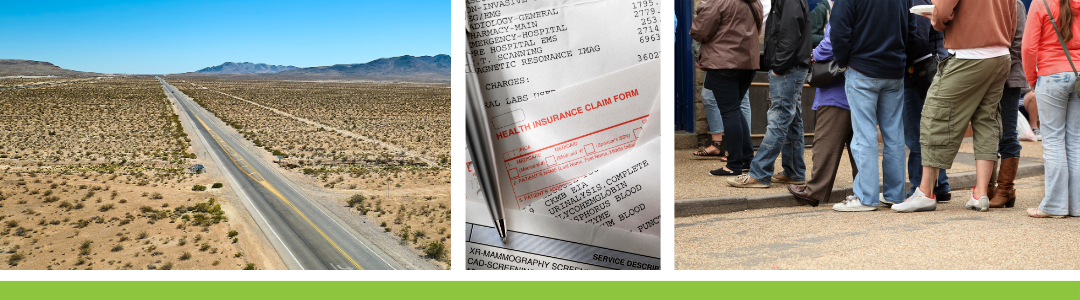

Access to Healthcare and Geography

Access to healthcare in Nevada is a challenge to many, including those living in rural communities, who are uninsured or underinsured, who lack reliable transportation, or who have lower health literacy or lack of trust in the existing healthcare landscape. Nevada’s healthcare system is decentralized throughout much of the state, with cancer care delivered almost entirely in urban centers and cancer screening services limited in rural and frontier communities. In many states, healthcare systems offer an organized network of people, institutions, and resources to deliver coordinated and comprehensive care. However, in Nevada there are very few of these systems in place, and they are almost wholly focused in urban centers, leaving many to navigate the healthcare landscape with less support.

Nevada has also long faced a shortage of healthcare professionals, with the majority of Nevadans living in federally designated healthcare professional shortage areas. Over the past decade, the number of active licensed primary care physicians per 100,000 population has declined after a short-lived increase in 2019. In 2024 there were 65.9 active primary care physicians per 100,000 residents in Nevada, with just 60.1 per 100,000 in rural and frontier counties,xviii whereas the national average is closer to 86 direct patient care primary care physicians per 100,000.xix Specialists, including oncologists, geneticists and genetic counselors, pediatric specialists and subspecialists, radiologists, and many others, are also in short supply across the state.

Nevada’s Division of Insurance adopted the Federal 2026 Network Adequacy Standards for qualified health plans to ensure insurers maintain a network of healthcare professionals that is sufficient to provide a plan’s covered services. The baseline standards set adequate access to primary care clinicians as within 10 miles in metropolitan counties and within 30 miles in rural counties. However, 11 of Nevada’s rural counties qualify for alternative standards for many clinician types. In six counties, adequate access according to standards could result in a 60–80-mile drive to visit a primary care clinician for adults and up to 240 miles for a pediatrician. Access to oncology services is considered adequate at a distance of anywhere from 60 to 90 miles in some rural counties, or as much as 240 miles for counties with extreme access considerations.xx

Nevada’s congressional and state representatives have championed numerous policies designed to train, attract, and retain qualified physicians and nurses, including incentives to practice in rural communities and tuition reimbursement in exchange for a commitment to work in a health professional shortage area. State legislators have passed bills to expand licensure of health professionals, among other efforts, resulting in many more advanced practice registered nurses in the state. Nevada has seen a 56% increase in medical school enrollment over the past decade,xxi nearly twice the national average, and Nevada’s senators are advocating for a greater allotment of graduate medical education slots. However, Nevada must also work to retain physicians trained in the state. In 2023, barely 33% of medical school graduates stayed in Nevada to practice medicine and just 53% of those who completed graduate medical education in Nevada stayed in the state.xxii While there is room for improvement, these results show that with continued effort the state can attract and retain medical students and physicians to reduce healthcare professional shortages.

Accessing healthcare, however, is more than just being able to make an appointment with a doctor. Many people face transportation barriers that keep them from seeking the care they need. In a 2024 survey of people living in rural and frontier communities across the West, researchers at Huntsman Cancer Institute found that 49% of those in Nevada could not get the healthcare they needed near their home.xxiii More than half of respondents in rural and frontier communities in Nevada visited a doctor or other health professional in the last year, but the likelihood went down as their remoteness increased. Fewer than a third had seen a doctor in the past year for a check-up or physical.xxiv

The same study found that Nevadans in rural and frontier communities often traveled 45 minutes—and sometimes up to 2 hours and 45 minutes—to get screened for cancer. Treatment for a serious condition, such as cancer, requires on average three hours of travel, but for some it can be up to four hours. Residents who responded said they were willing to travel for these services, but often the time to reach healthcare was more than they would like to spend traveling.xxv Expansion of telehealth is a way to bring healthcare closer to home, and about half of rural and frontier Nevadans said they used email or the internet to communicate with a doctor’s office or look up test results. However, 7% of survey respondents in Nevada’s rural and frontier communities said they didn’t have internet access at home, restricting their ability to use telehealth.xxvi Nevada’s Office of Science, Innovation, and Technology has prioritized expanding high-speed internet to underserved and unserved areas across the state, however development of infrastructure and deployment of service takes time and telehealth access will continue to remain a challenge for some during this plan’s timeframe.xxvii

A lack of health insurance is another barrier an estimated 10.8% of Nevadans have in accessing healthcare, based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey.xxviii This figure represents a steady decline in the percentage of uninsured Nevadans over the past fifteen years following implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion in Nevada. Nevadans ages 19-54 are more likely to be uninsured, as are individuals who lack a high school diploma, or who are Hispanic or Latino, American Indian, or mixed race.xxix More than one-third of Nevadans who are uninsured have incomes two to four times the federal poverty level, earning enough to disqualify them from Medicaid but not enough to afford health insurance and not receiving employer-sponsored health insurance.xxx Additionally, although people who are Hispanic or Latino account for 30% of Nevada’s population, they account for more than half of those who are uninsured.xxxi

During the COVID-19 pandemic the rate of people who were uninsured increased slightly, due largely to job loss and either the loss of employer-sponsored healthcare or the inability to pay for marketplace insurance policies, but the increase was short-lived. The public health emergency also suspended typical re-enrollment eligibility requirements, greatly expanding the number of people who were able to access healthcare with Medicaid coverage. The number of Nevadans covered by Medicaid has declined gradually since mid-2023, and enrollment as of January 2025 was just under 792,000.xxxii

Medicaid is a cornerstone of cancer control efforts in Nevada, particularly for low-income, uninsured, and underserved populations. Nevada is one of 41 jurisdictions that approved Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. The state’s Medicaid program provides routine healthcare, including cancer screening and treatment, for hundreds of thousands of Nevadans and helps to alleviate the financial burdens associated with treatment of cancer and other chronic diseases, for the state and those who are insured, by supporting disease prevention and early detection, both of which lead to lower costs for treatment and improved outcomes.

xviii Nevada Instant Atlas. Nevada Office of Statewide Initiatives, https://med2.unr.edu/SI/CountyData/atlas.html.

xix Association of American Medical Colleges. 2024 Key Findings and Definitions. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2024-key-findings-and-definitions.

xx Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Network Adequacy, Baseline and Alternative Time and Distance Standards, 18 Apr. 2025, https://www.qhpcertification.cms.gov/QHP/applicationmaterials/Network-Adequacy.

xxi Association of American Medical Colleges. U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/report/us-physician-workforce-data-dashboard.

xxii Association of American Medical Colleges. U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/report/us-physician-workforce-data-dashboard.

xxiii Onega, T., et al. Community Health Assessment Survey: Rural & Frontier. University of Utah Health and Huntsman Cancer Institute, 2025.

xxiv Onega, T., et al. Community Health Assessment Survey: Rural & Frontier. University of Utah Health and Huntsman Cancer Institute, 2025.

xxv Onega, T., et al. Community Health Assessment Survey: Rural & Frontier. University of Utah Health and Huntsman Cancer Institute, 2025.

xxvi Onega, T., et al. Community Health Assessment Survey: Rural & Frontier. University of Utah Health and Huntsman Cancer Institute, 2025.

xxvii Nevada Governor’s Office of Science, Innovation and Technology. Broadband, 2025, https://osit.nv.gov/Broadband/Broadband/.

xxviii U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2023.

xxix U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2023.

xxx Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts. https://www.kff.org/statedata/custom-state-report/?i=32245%7Cf788d986&g=nv&view=3.

xxxi Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts. https://www.kff.org/statedata/custom-state-report/?i=32245%7Cf788d986&g=nv&view=3.

xxxii Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. Monitoring Medicaid Enrollments, Disenrollments, and Renews in Nevada Dashboard, 2025, https://app.powerbigov.us/view?r=eyJrIjoiNWE2NWJjNDctZDJiMy00ZmRjLWJhMTktNDI3NzMyYmUwYTVkIiwidCI6ImU0YTM0MGU2LWI4OWUtNGU2OC04ZWFhLTE1NDRkMjcwMzk4MCJ9.

Public Health Infrastructure

Over the past five years, Nevada’s public health infrastructure has seen notable developments driven by both necessity and strategic planning. The COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted the importance of healthcare and public health and resulted in numerous changes. These included modernization and expansion of local health districts, a first-ever statewide health improvement plan, investment in new health facilities, and data and technology enhancements to improve surveillance, reporting, and decision-making with regards to infectious and chronic diseases. This progress, however, is tempered by ongoing funding challenges and political upheaval.

Nevada’s Silver State Health Improvement Plan (SSHIP), released in 2023, called for modernization and improvement of the state’s data collection, analysis, and dissemination and resulted in investments in the Nevada Central Cancer Registry and the Department of Health and Human Service’s Office of Analytics. Together, these two departments have moved to enhance cancer data collection through improvements to cancer reporting systems and have launched online dashboards to share cancer incidence and mortality data. However, opportunities are available to increase data collection through cloud-based and interoperable systems, and by collecting additional data, such as sexual orientation, gender identity, and clinical trials participation. More extensive data reporting, including robust epidemiological review, would improve Nevada’s ability to understand its cancer burden and respond accordingly. In fact, the lack of thorough epidemiologic review of Nevada’s cancer burden limits the ability of cancer control and other public health professionals to respond to the needs of Nevadans.

Nevada’s SSHIP also called for greater investment in the state’s public health system with funding that is “appropriate, flexible, and sustainable.” Much of Nevada’s public health infrastructure—notably, state program staff—is funded through federal grants, with inadequate investment from the state. Federal funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) support the Nevada Central Cancer Registry, Women’s Health Connection breast and cervical screening program, Comprehensive Cancer Control Program, and much of its Tobacco Control Program, and, through subgrants from the State, community nonprofits tasked with leading and executing much of Nevada’s cancer control efforts.

Environmental Exposures

Often called “ecological determinants of health,” planetary health and environmental factors have a wide-ranging impact on human health, cancer control, and the ability for healthcare systems to operate. These factors are often interconnected and can include extreme weather, air and chemical pollution, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, or resource scarcity, and they have the potential to affect human health directly or indirectly, or to cause disruptions to infrastructure and systems that are vital to healthcare.

Climate change, characterized by long-term shifts in global temperatures and weather patterns, is a well-documented environmental factor in Nevada. The state is home to the two fastest-warming cities in the nation: Las Vegas and Reno. Both cities are affected by urban heat islands, which are areas within a city that experience higher temperatures than surrounding rural areas, particularly during the night. These urban heat islands are caused by a combination of development and built environments such as buildings and roads that attract and retain heat and human activity that generates heat, such as operating vehicles. In comparing the past 30 years to the previous 30 years, National Weather Service data shows that annual mean low temperatures in Las Vegas increased up to seven degrees and mean high temperatures increased up to one degree. Elevated temperatures in these zones increase ozone and particulate pollution, both linked to higher cancer risks, particularly lung cancer. Extreme heat also prevents people from participating in outdoor physical activity and can limit mobility. Recent research has mapped urban heat islands in both citiesxxxiii and shows that areas most affected by heat islands are more likely to be found in predominately lower-income and non-white communities.xxxiv

More extreme weather—including drier conditions, more intense winds, and rising temperatures—have also contributed to more frequent and larger wildfires across the West. Wildfire smoke is now the dominant source of particulate pollution during fire season in Nevada. This particle pollution is known as PM2.5, which refers to particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less, has increased from about 11 days of high PM2.5 every four years to about 17 days each year.xxxv There is a 9% increase in lung cancer incidence or mortality for every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5. Wildfires, especially those that burn through buildings, vehicles, and other non-plant materials, also emit pollutants, including human carcinogens, that can contaminate water and soil and thus remain in the environment long after air quality improves.xxxvi

Threats from heat, extreme weather, and wildfire have the potential to affect more than just air quality and ambient temperatures. These factors can result in disruptions to community infrastructure including power, water, and roads, which can threaten access to healthcare, disrupt supply chains, and hamper food production at farms and ranches. Industrialized food production, which is threatened by climate change-related disruptions, also contributes to climate change through the clearing of land, greenhouse gas emissions from machinery and animals, emissions from production and transportation, and pollution from fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, packaging, and production.xxxvii Researchers have linked agricultural pesticides to increased rates of bladder cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma in Nevada, and to a lesser extent increased rates of lung, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers, and have suggested the association between cancer and pesticides is comparable to smoking for some cancer types.xxxviii Agriculture contributes significantly to Nevada’s economy, specifically to many rural communities, and is primarily focused on cattle and alfalfa production. However, several crops are grown in the state including potatoes, barley, wheat, corn, oats, onions, garlic, and smaller crops of fruits and vegetables.xxxix

Mining is another key industry in Nevada, with gold, copper, and lithium extracted from the earth, among other ores. Many types of mining use chemicals that have the potential to pollute the water, soil, and air, and that have been linked with increased risk of cancer. These chemicals include cyanide, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and lead, some of which are linked to skin, lung, bladder, kidney, prostate, and breast cancer.xl There are more than two dozen gold mines in the state, including some of the largest open-pit gold mines in North America and open-pit gold mining is one of the highest potential mining threats to the environment.xli While Nevada regulates emissions in modern mining operations to mitigate risk, legacy contamination remains a challenge.

Many of these ecological determinants intersect with social and economic factors, amplifying cancer disparities. Often, the use of chemicals in the environment—whether for agriculture, mining, military, or some other use—affects individuals of color, those in indigenous or rural communities, and those with less access to healthcare. For example, the Yerington Paiute Tribe’s water supply is contaminated with carcinogens including arsenic, chromium, and uranium from the former Anaconda Copper Mine in Lyon County, now designated by the Environmental Protection Agency as a Superfund site because of the contamination.xlii Residents at the Duck Valley Indian Reservation in Owyhee, who are members of the Shoshone Paiute Tribe, have been exposed to years of contamination from two federal Bureau of Indian Affairs buildings that in 1985 leaked thousands of gallons of heating oil, and also were the source of contamination from arsenic, copper, lead, cadmium, and the two chemicals that make up Agent Orange, which were both used in the 1970s as herbicides in the area’s canal system. Epidemiologists from American Cancer Society have said linking specific cancer cases to the chemical exposure would be complicated and more research needs to be conducted. Despite this, the tribe has logged hundreds of illnesses over more than three decades that could be cancer.xliii

While naturally occurring, radon is no less threatening than other environmental factors in its risk for causing lung cancer. Radon is a colorless, odorless, tasteless radioactive gas that is formed from the breakdown of uranium and radium in soil, rock, and water. It is present at varying levels in Nevada with some communities more affected than others. The best way to reduce the risk of radon-related lung cancer is to test and mitigate homes, schools, and workplaces for radon gas.xliv

Research is ongoing as to the carcinogenic effect of many substances in our environment. However, cancer control efforts can address this broad spectrum of ecological determinants while prioritizing health equity for the state’s most vulnerable populations. This can be achieved through ongoing research and policy action to mitigate risks and improve access to effective prevention, early detection, treatment, and survivorship resources across diverse environments.

Reducing one’s personal exposure to environmental carcinogens can be one of many things a person does to lower their risk of cancer. This might look like:

- Limiting exposure to PFAS (Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances) by using water filters certified to remove PFAS and supporting stricter regulations on PFAS in consumer products and industrial emissions.

- Testing well water to verify water quality.

- Supporting policies to reduce outdoor air pollution and wildfires to reduce the amount of cancer-causing PM2.5 (fine particulate matter) in the air and wearing an N95 face mask during periods of poor air quality.

- Washing fruits and vegetables thoroughly to remove pesticide residues, using protective equipment when working with pesticides and herbicides, or supporting safer alternatives to pest and weed management.

- Advocating for workplace protections that reduce exposure to carcinogens through improved policies and regulations.

- Testing and mitigating homes, schools, and places of work for radon and other carcinogenic materials.

xxxiii Heat.gov. National Integrated Heat Health Information System. https://www.heat.gov/pages/nihhis-urban-heat-island-mapping-campaign-cities.

xxxiv City of Las Vegas Community Dashboard. https://communitydashboard.vegas/neighborhood.

xxxv Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Wildfire Smoke in the Reno Metro Area. https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023-wildfire-smoke-impact-snapshots-reno.pdf.

xxxvi Wilgus, M. L., and M. Merchant. "Clearing the Air: Understanding the Impact of Wildfire Smoke on Asthma and COPD." Healthcare (Basel), vol. 12, no. 3, 25 Jan. 2024, p. 307, doi:10.3390/healthcare12030307.

xxxvii Nogueira, Leticia M. "The Climate and Nature Crisis: Implications for Cancer Control." JNCI Cancer Spectrum, vol. 7, no. 6, Dec. 2023, pkad091, https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkad091.

xxxviii Gerken, J., et al. "Comprehensive Assessment of Pesticide Use Patterns and Increased Cancer Risk." Frontiers in Cancer Control and Society, vol. 2, 2024, doi:10.3389/fcacs.2024.1368086.

xxxix Nevada Department of Agriculture. Agriculture in Nevada. Accessed 15 June 2025, https://agri.nv.gov/Administration/Administration/Agriculture_in_Nevada/.

xl Huerta, D., et al. "Probabilistic risk assessment of residential exposure to metal(loid)s in a mining impacted community." Science of the Total Environment, vol. 872, 2023, p. 162228, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162228.

xli Abdul-Wahab, Sabah, and Fouzul Marikar. "The environmental impact of gold mines: pollution by heavy metals." Open Engineering, vol. 2, no. 2, 2012, pp. 304-313, https://doi.org/10.2478/s13531-011-0052-3.

xlii U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Interim Record of Decision Anaconda Copper Mine Site. July 2017, https://ndep.nv.gov/uploads/land-aml-docs/20180205_ACMS_IAOC_App_E_ROD-1.pdf.

xliii Stern, G. "A Remote Tribe is Reeling from Widespread Illness and Cancer. What Role Did the U.S. Government Play?" Associated Press, 10 Sept. 2024, https://www.ap.org/news-highlights/spotlights/2024/a-remote-tribe-is-reeling-from-widespread-illness-and-cancer-what-role-did-the-us-government-play/.

xliv Nevada Radon Education Program. "What is Radon." 2025, https://extension.unr.edu/radon/what-is-radon.aspx.